The Swedish Migration Agency answers: Unaccompanied minors – how have asylum applications evolved over the past ten years?

From tens of thousands to a few hundred per year – the number of asylum-seeking unaccompanied minors and young people who come to Sweden has declined sharply over the past decade.

Since 2013, almost 50,000 children and young people have come to Sweden to seek protection without an accompanying parent or other guardian. The numbers reached their peak in 2015, when more than 30,000 asylum-seeking unaccompanied minors came here, after which the number of applicants fell rapidly, and in recent years around 500 children and young people seek protection in Sweden each year.

About half of these 50,000 children were granted asylum, and just under 18,000 had their applications rejected (the remaining cases were written off, dismissed, annulled or similar).

.png) Zoom image

Zoom imageThe diagramme shows the number of unaccompanied children applying for asylum each year, and whose applications have been granted or denied, 2013-2023.

Significantly more boys than girls

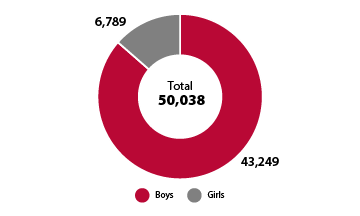

The vast majority of unaccompanied minors who came to Sweden were teenagers when they applied for protection. From 2013–2023, 48,000 of the applicants were between 12 and 17 years old when they applied for a residence permit. The vast majority of the applicants were boys — just over 43,000 boys, compared to just under 7,000 girls.

The tendency has been that the younger the applicants are, the smaller the difference is between the number of boys and girls. Among the youngest children (aged 0–5) — a very small group — there are almost as many girls as boys. In the group of 6–11-year-olds, there are about twice as many boys — 1,699 of them, compared to 957 girls. The largest group is teenagers (aged 12–17), in which there are significantly more boys than girls — 41,224 of them, compared to 6,789 girls.

.png)

Different countries of origin

The dominant country of origin has shifted over the years, but Afghanistan, Syria, Morocco, Somalia and Eritrea are all high on the list. At least, this was the case until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2021, after which Ukrainian applicants have accounted for the majority of Sweden’s asylum cases, including among unaccompanied minors and young people. In 2015, Afghanistan stood out; at that time, just under 21,000 asylum-seeking unaccompanied minors were Afghan, i.e. two out of three applicants.

.png)

30,000 unaccompanied minors in 2015

From 2013 to 2024, the majority of asylum-seeking children and young people came to Sweden during the refugee crisis of 2015. In the autumn of the same year, border controls and stricter legislation were introduced, after which the number of asylum seekers decreased sharply. This was particularly true of unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors and young people, whose numbers rapidly declined. In recent times, around 500 children without an accompanying parent or other guardian apply for protection in Sweden each year.

Statistics from the Swedish Migration Agency and Statistics Sweden show that of the large group of unaccompanied minors who came to the country in 2015, around 20,000 of them are still in Sweden today. 7,300 have become Swedish citizens, and just under 5,000 have left the country. About 13,000 of the applicants received asylum, while over 7,000 received a residence permit under the Upper Secondary School Act. A report on these unaccompanied minors published last year (in Swedish) External link, opens in new window. indicates that eight out of ten were employed, that most had received upper secondary education (but often without earning a diploma) and that many worked in health and social care.

External link, opens in new window. indicates that eight out of ten were employed, that most had received upper secondary education (but often without earning a diploma) and that many worked in health and social care.

A temporary Upper Secondary School Act

After a quarter of a million asylum seekers arrived in Sweden from 2014–2015, the Swedish Migration Agency’s processing times increased sharply, and for some unaccompanied children and young people, this meant that their cases were examined after they turned 18 — and thus considered as adults.

After major political discussion, a series of temporary regulations known as the “Upper Secondary School Act” were adopted, allowing unaccompanied young people whose asylum applications were rejected to remain in Sweden to study at the upper secondary school level. The Upper Secondary School Act also offered those who can support themselves within six months of completing their upper secondary school studies the opportunity to be granted a permanent residence permit.

The Upper Secondary School Act has been gradually phased out, and since December 2023 it is no longer possible to be granted a residence permit on the basis of studies at the upper secondary school level. As of 20 July 2024, a residence permit cannot be extended to look for work after upper secondary school, but until 19 January 2025, a person who has graduated upper secondary school and who can support themselves through work can apply for a permanent residence permit.

What Sweden’s reception of unaccompanied minors looks like today

For the approximately 500 unaccompanied minors under the age of 18 who seek protection in Sweden each year, special rights and support apply during the application process. Among other things, they are given a guardian who represents them in all personal as well as financial and legal matters, and early in the process they are assigned to a municipality that is responsible for their accommodation, schooling, etc.

Children who abscond

Every year, a number of unaccompanied minors and young people under the age of 18 disappear. The number varies; in recent years, between 80 and 100 have absconded annually, but for 2015, 2,420 are recorded as having absconded.

These children risk being subjected to human trafficking, sexual exploitation and the like. To address these problems and find out why and where the children disappear, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, the Swedish Migration Agency, and the Swedish Police Authority have launched a joint development project. To ensure that fewer children disappear, these authorities must work together to increase competence and develop their cooperation.